Tiempo de lectura: 30 minutos

El irregular uso de los cohetes Congreve en las Guerras Napoleónicas en el campo de batalla mezcló algunos éxitos remarcables con varias experiencias fallidas. Ello se debió a su poca fiabilidad – los cohetes tenían la desagradable costumbre de curvarse en el aire y volver a estallar a los pies de quienes los utilizaban – y a la lógica comparación con los disparos de los cañones tradicionales.

William Congreve Jr., el «inventor» o mejor dicho «adaptador» de los cohetes británicos de la época aceptaba que los cohetes fueron inventados por algunos «héroes de la antigüedad china», mientras que su aplicación en la guerra pertenecía a las «remotas edades del imperio mogol». Sin embargo, como nadie en Inglaterra era capaz de fabricarlos, reivindicó la prioridad del invento:

«El único mérito que reclamo, como autor del sistema de cohetes en este país, es que obtuve de la potencia del cohete, por una justa combinación de sus partes… alcances, y poder de transportar pesos infinitamente más allá de cualquier cosa jamás concebida… o conocida en la India, donde han sido usados… desde tiempo inmemorial. Pero, ¿qué son los cohetes indios comparados con los nuestros? [5]

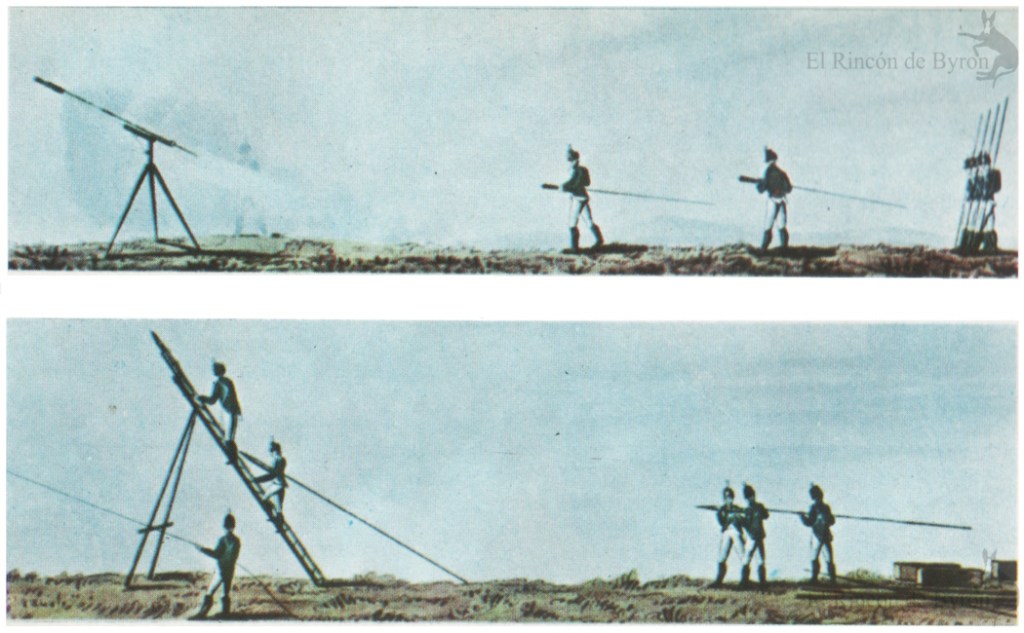

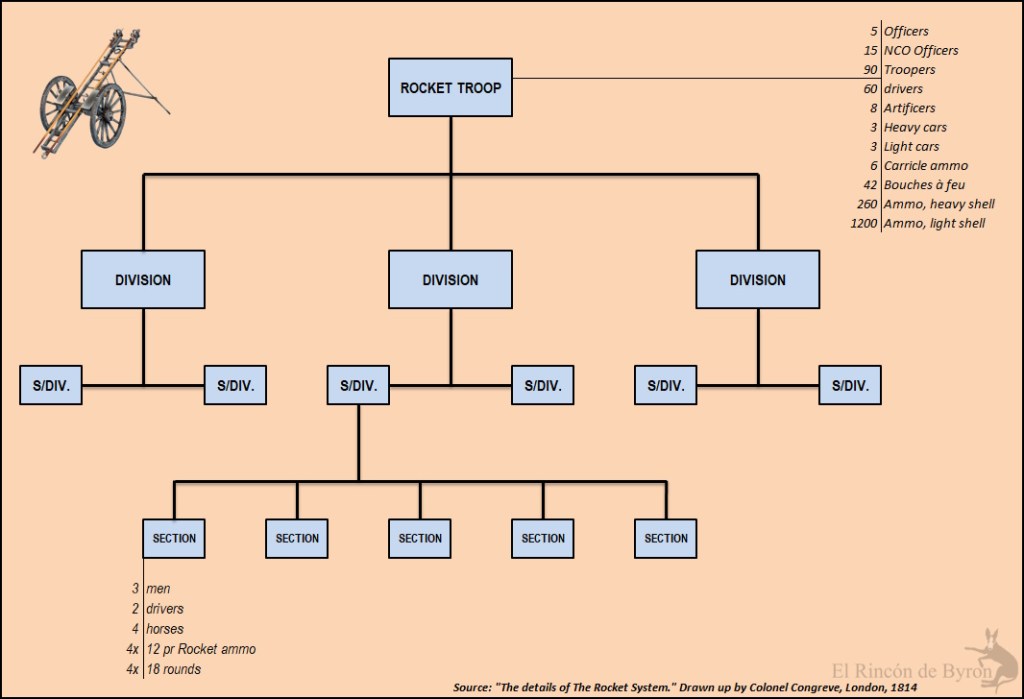

Las únicas unidades de artillería de campaña del ejército británico que utilizaron cohetes fueron los destacamentos especialmente formados de la Real Artillería a Caballo que evolucionaron hasta convertirse en las Tropas de Cohetes nº 1 y nº 2. Disparaban los cohetes de proyectil de 12 libras sobre el terreno y las tropas estaban equipadas con un carro cohete de armazón de escalera para disparar los cohetes de carcasa de 32 libras con fines de bombardeo. [1]

The irregular use of Congreve rockets in the Napoleonic Wars on the battlefield mixed some remarkable successes with several failed experiences over the years. This was due to their unreliability – the rockets had a nasty habit of curling up in the air and exploding again at the feet of those who used them – and the logical comparison with the field guns fire used.

William Congreve Jr., the «inventor» or rather «adaptor» of British rockets at the time, accepted that rockets were invented by some «heroes of Chinese antiquity», while their application in warfare belonged to the «remote ages of the Mughal Empire». However, since no one in England was capable of making them, he claimed priority for the invention:

«The only merit I claim, as the author of the rocket system in this country, is that I obtained from the power of the rocket, by a just combination of its parts . . . ranges, and power of carrying weights infinitely beyond any thing ever before conceived… or known in India, where they have been used… time out of mind. But what are the Indian rockets compared to our own? [5]

The only field artillery units to use rockets in the British Army were the specially formed detachments of the Royal Horse Artillery which evolved into the in No. 1 and No. 2 Rocket Troops. They discharged the 12-pr shell rockets along the ground and the troops were equipped with a ladder frame rocket car to discharge the 32-pr carcass rockets for bombardment purposes. [1]

INTRODUCCIÓN / INTRODUCTION

Al parecer, la utilización de los cohetes de pólvora en los campos de batalla se originó en China, probablemente como un lógico desarrollo en el tiempo del descubrimiento de la pólvora en el siglo XIII y de su uso en algunas épocas del imperio mongol. Debido a las conexiones por las rutas comerciales su existencia fue conocida posteriormente en Oriente Medio y Europa ya con anterioridad al siglo XIV, pero fue en la India donde el cohete se desarrolló y perfeccionó utilizándose como un arma antipersonal incendiaria, principalmente contra masas de caballería o elefantes.

A finales del siglo XVIII, como consecuencias de los conflictos entre la compañía Británica de las Indias Orientales y el reino de Mysore, en la India, se dió origen a una serie de conflictos conocidos como guerras Anglo-Mysore, entre los años 1767 y 1799. Concretamente, en la tercera y cuarta campañas, en las batallas de Seringapatam (1792 y 1799) las tropas británicas en la India junto con sus aliados locales fueron atacadas con cohetes de pólvora por las tropas de Tipu Sultan (que asimismo recibía apoyo por parte de Francia en forma de armamento y mercenarios). Los oficiales británicos, impresionados con los efectos de esta arma enviaron algunas muestras al Museo-Depósito de la Real Artillería, cerca del Arsenal Real en Woolwich, que había sido fundado en 1778 por el entonces capitán Sir William Congreve.

Allí también se encontraba el hijo de Congreve, William Congreve Jr., que encontró por primera vez con algunos de los dispositivos con los que se dedicaría denodadamente los años siguientes a intentar perfeccionar los cohetes utilizados por los indios. William preveía su uso tanto en combates navales como terrestres, pudiendo aplicar el poder multiplicador de la fuerza explosiva en lugares donde la artillería tradicional por espacio no podia utilizarse, bien fuera por la equipación requerida y o por el retroceso de sus efecto explosivo. En su libro «The Details of the Rocket System» («Los detalles del sistema de cohetes»), publicado en 1814, William Congreve ya manifestaba que perfeccionó su invento ya en el año 1805.

Los cohetes Congreve se componían de un cilindro de hierro que contenía pólvora negra, similar a la pólvora de cañón, ya que se fabricaba con azufre, salitre y carbón vegetal, pero en cantidades diferentes. La pólvora negra se encendía mediante una mecha, que proporcionaba la propulsión al cohete. Los cohetes se sujetaban a palos guía de madera para estabilizar su vuelo y se lanzaban de dos en dos desde medias canaletas montadas en simples armazones metálicos en forma de «A». Se accionaba un mecanismo de pedernal tirando de una larga cuerda que activaba dos espoletas: una encendía la pólvora negra de la carcasa de hierro que generaba el empuje, mientras que la otra espoleta recorría el exterior de la carcasa de hierro para encender la ojiva situada en la parte superior. [13]

Congreve no dejaba de subrayar las ventajas de sus cohetes: aparte del menor coste, un tubo de lanzamiento para un proyectil de 5 kg no pesaba más de 9 kilogramos, y necesitaba de un solo hombre, mientras que para lanzar el mismo peso en un proyectil de artillería hacía falta el empleo de un cañón de 750 kg. con el empleo de varios hombres.

The use of gunpowder rockets on battlefields seems to have originated in China, probably as a logical development in the time of the discovery of gunpowder in the 13th century and its use in some periods of the Mongol empire. Due to trade route connections its existence was subsequently known in the Middle East and Europe prior to the 14th century, but it was in India that the rocket was developed and perfected for use as an incendiary anti-personnel weapon, mainly against masses of cavalry or elephants.

In the late 18th century, conflicts between the British East India Company and the kingdom of Mysore in India led to a series of conflicts known as the Anglo-Mysore wars between 1767 and 1799. Specifically, in the third and fourth campaigns, at the Battles of Seringapatam (1792 and 1799), British troops in India along with their local allies were attacked with powder rockets by the troops of Tipu Sultan (who also received support from France in the form of arms and mercenaries). British officers, impressed with the effects of this weapon, sent some samples to the Royal Artillery Museum-Depot near the Royal Arsenal at Woolwich, which had been founded in 1778 by the then Captain Sir William Congreve.

Congreve’s son William Congreve Jr. was also there, and he first encountered some of the devices with which he would spend the next few years trying to perfect the rockets used by the Indians. William envisaged their use in both naval and land engagements, being able to apply the multiplied power of the explosive force in places where traditional artillery could not be used for space, either because of the equipment required or because of the recoil of their explosive effect. In his book «The Details of the Rocket System», published in 1814, William Congreve stated that he had perfected his invention as early as 1805.

Congreve Rockets were made up of an iron case containing black powder, which was similar to gun powder in that it was made from sulphur, saltpetre and charcoal – but in different quantities. The black powder would be ignited via a fuse, which would provide the propulsion for the rocket. The rockets were attached to wooden guide poles to help stabilise their flight and were launched in pairs from half troughs on simple metal A-frames. A flintlock mechanism was triggered by pulling a long cord, which would trigger two fuses; one would ignite the black powder in the iron case creating the thrust, whilst the other fuse ran around the outside of the iron casing to ignite the warhead at the top. [13]

Congreve did not fail to emphasize the advantages of his rockets: apart from the lower cost, a launching tube for a 5 kg projectile weighed no more than 9 kg and required only one man, whereas to launch the same weight in an artillery projectile required the use of a 750 kg cannon and the employment of several men.

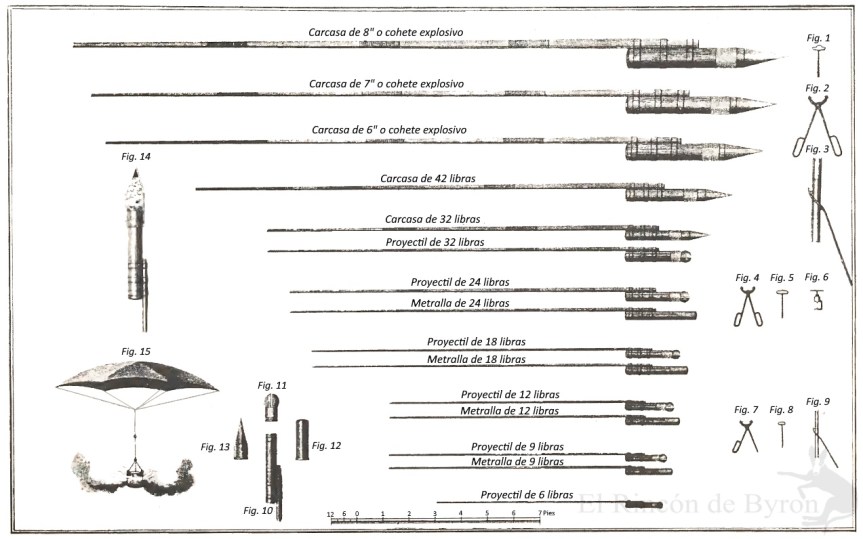

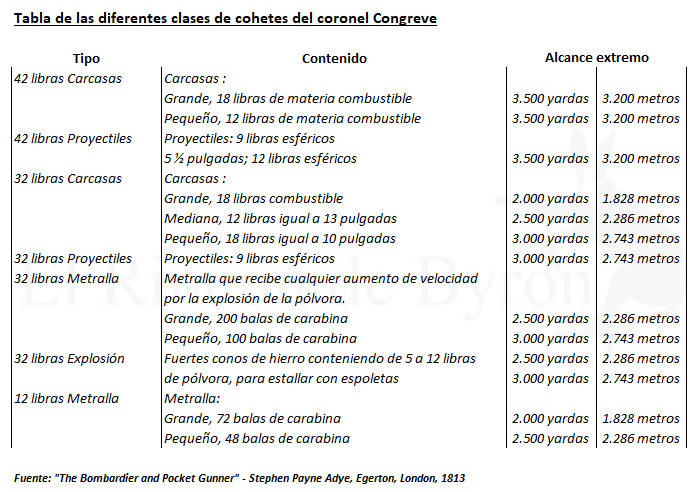

Los proyectiles de 42 y 32 libras se dedicaban principalmente a los bombardeos. Fig. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. 7, 8. y 9, representan los diferentes implementos utilizados para unir los palos, o fijarlos al cohete, siendo de diferentes tamaños, en proporción a las diferentes clases a las que pertenecen. Las figuras 10, 11, 12 y 13 representan otro modo de disponer las diferentes clases de municiones. Así, la Fig. 10 es el cohete, y las fig. 11, 12 y 13, son respectivamente un proyectil, una bala metralla o una carcasa. Las figuras 14 y 15 representan el proyectil derecho o la carcasa flotante. [15] (c)

The 42-pounders and 32-pounders were mainly used for bombing. Fig. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. 7, 8. and 9, represent the different implements used for jointing the sticks, or fixing them to the Rocket, being of different sizes, in proportion to the different natures to which they belong. Fig. 10, 11, 12, and 13, represent another mode of arranging the different natures of ammunition. Thus, Fig. 10 is the Rocket, and Fig. 11 , 12, and 13, are respectively a shell, case shot, or carcass. Fig. 14 and 15 represent the right ball or floating carcass Rocket. [15] (c)

DE LOS PERIÓDICOS A LOS COHETES / FROM NEWSPAPERS TO ROCKETS

Sir William Congreve, Jr. nació el 20 de mayo de 1772 en Londres, Inglaterra. Era el hijo mayor del Teniente General Sir William Congreve, Su padre era el interventor de los Laboratorios Reales en el Arsenal Real. Congreve pasó su educación en Hackney, en la escuela de Newcome, en la Wolverhampton Grammar School y en Singlewell, en Kent. Tras estudiar Derecho, se licenció en 1793 y en 1796 en el Trinity College.

En 1803, Congreve se alistó como voluntario en la London and Westminster Light Horse y se convirtió en un hombre de negocios que publicaba un controvertido periódico, el «Royal Standard and Political Register», de carácter progubernamental. En 1804, Congreve sufrió una difamación pública, por lo que decidió dejar de publicar el periódico y empezó sus experimentos con cohetes en el Real Laboratorio de Woolwich.

En 1805, Congreve hizo una demostración de sus primeros cohetes de combustible sólido en el Arsenal Real. Su trabajo se consideró lo suficientemente avanzado como para participar en dos ataques contra objetivos enemigos. En 1811, Congreve recibió el rango honorífico de teniente coronel de la artillería del ejército de Hanover y más tarde se convirtió en general de división del mismo ejército. En 1814 y 1821, Congreve organizó en Londres impresionantes espectáculos pirotécnicos con motivo de la paz y la coronación de Jorge IV, respectivamente. Congreve realizó varios inventos aparte de los cohetes Congreve. Se dedicó a ser inventor hasta su muerte. Llegó a registrar 18 patentes, de las cuales dos eran para cohetes.

Se convirtió en el interventor del Real Laboratorio de Woolwich desde 1814 hasta su muerte. En diciembre de 1824, Congreve pudo casarse con Isabella Carvalho en Wessel, Prusia. y tuvieron tuvieron dos hijos y una hija. Ese mismo año, Congreve se convirtió en director general de la Asociación Inglesa para el Alumbrado por Gas en el Continente, para producir gas para varias ciudades de la Europa continental.

Sir William Congreve, Jr. murió en Toulouse, en mayo de 1828, Francia, a la edad de 55 años. [9]

Sir William Congreve, Jr. was born on 20 May 1772 in London, England. He was the eldest son of Lieutenant General Sir William Congreve. His father was the comptroller of the Royal Laboratories at the Royal Arsenal. Congreve spent his education in Hackney, at Newcome School, Wolverhampton Grammar School and Singlewell in Kent. After studying law, he graduated in 1793 and in 1796 from Trinity College.

In 1803, Congreve enlisted as a volunteer in the London and Westminster Light Horse and became a businessman who published a controversial newspaper, the pro-government «Royal Standard and Political Register». In 1804, Congreve suffered a public libel, so he decided to stop publishing the paper and began his rocket experiments at the Royal Laboratory at Woolwich.

In 1805, Congreve demonstrated his first solid-fuel rockets at the Royal Arsenal. His work was considered sufficiently advanced to participate in two attacks on enemy targets. In 1811, Congreve received the honorary rank of lieutenant colonel of the Hanoverian army artillery and later became a major general in the same army. In 1814 and 1821, Congreve organised impressive fireworks displays in London on the occasion of the peace and the coronation of George IV, respectively. Congreve made several inventions in addition to the Congreve rockets. He devoted himself to being an inventor until his death. He registered 18 patents, two of which were for rockets.

He became the comptroller of the Royal Woolwich Laboratory from 1814 until his death. In December 1824, Congreve was able to marry Isabella Carvalho in Wessel, Prussia, and they had two sons and a daughter. In the same year, Congreve became general manager of the English Association for Gas Lighting on the Continent, to produce gas for various cities in continental Europe.

Sir William Congreve, Jr. died in Toulouse, in May 1828, France, at the age of 55. [9]

Las primeras pruebas en el año 1804 habían sido desiguales y el primer uso en combate en 1805 en Boulogne contra la fuerza y flotas de invasion de Napoleón en la costa francesa fue un fracaso, lo que provocó un reguero de críticas implacables, pero con el apoyo político de alto nivel de los Congreve y el patrocinio del gobierno1, el proyecto tuvo otras oportunidades. Se proyectaron incursiones en Gaeta, cerca de Nápoles, en el Mediterráneo en abril de 1806 y también otra vez en Boulogne, en octubre de 1806 y aunque todo indica que el desenlace fue positivo en ambos casos (en Boulogne se dispararon cerca de 2.000 cohetes) no llegaron a tener la difusión requerida.

El punto de inflexion fue el asedio de Copenhague en 1807 por parte de la Royal Navy británica, donde las decenas de incendios provocados por las balas explosivas e incendiarias y el material combustible de los cohetes lanzados (esta vez del orden de unas 300 unidades2), resultaron ser un factor decisivo para obligar a los daneses a capitular.

Hubo otras tentativas de ataques contra los franceses en Aix o en la expedición de Walcheren y aunque las baterías terrestres bajo las órdenes directas del coronel Congreve ayudaron a capturar Flushing en agosto de 1809, la expedición en sí fue un fracaso. No sería hasta la Batalla de Leipzig, donde el único contingente presente del ejército británico con una unidad de cohetes tendría un destacado papel3.

Early trials in 1804 had been uneven and the first combat use in 1805 at Boulogne against Napoleon’s invasion force and fleets on the French coast was a failure, which provoked a barrage of relentless criticism, but with high-level political support from the Congreve and government sponsorship1, the project was given further opportunities. Raids were planned at Gaeta, near Naples, in the Mediterranean in April 1806 and again at Boulogne in October 1806, and although there was every indication that the outcome was positive in both cases (nearly 2000 rockets were fired at Boulogne), they did not achieve the required circulation.

The turning point was the siege of Copenhagen in 1807 by the British Royal Navy, where the dozens of fires caused by the explosive and incendiary bullets and the combustible material of the rockets launched (this time in the order of 300 units2), proved to be a decisive factor in forcing the Danes to capitulate.

There were other attempts to attack the French at Aix or in the Walcheren expedition, and although the land batteries under the direct orders of Colonel Congreve helped to capture Flushing in August 1809, the expedition itself was a failure. It was not until the Battle of Leipzig that the only British army contingent present with a rocket unit would play a prominent role3.

LOS COHETES CONGREVE EN LA PENINSULA / CONGREVE ROCKETS ON THE PENINSULA

Aunque pudiera parecer que el uso de los cohetes quedaba restringido al conflicto en Centroeuropa, A. D. McCaig (ver Fuentes) nos habla de las experiencias del teniente Lindsay y su unidad de cohetes Congreve en Portugal, en noviembre de 1810.

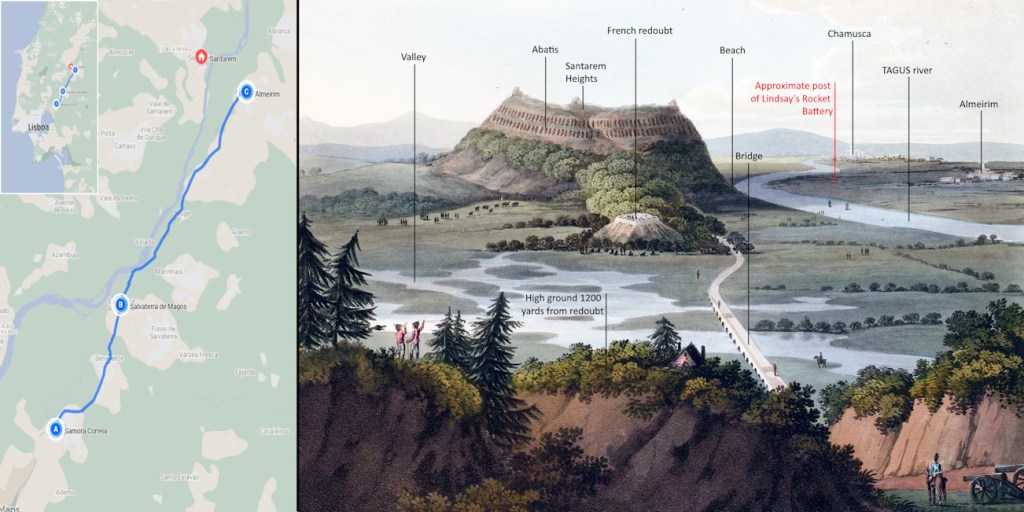

El teniente Lindsay había llegado a Portugal con una partida de cohetes y se hallaba en Zamora Borea (ó ¿Zamora Correia?) con sus proyectiles. Pensando que tendría suficientes mulas para el transporte, tuvo que contentarse con unas varas de bueyes, llegando su destino, Almeiria (Almeirim) el 11 de noviembre, a unos 6 kilómetros de Santarem, habiendo parado previamente en Salvatiera (Salvatierra de Magos) y viajando de noche para evitar las patrullas enemigas. Lindsay estaba acompañado por un grupo de sesenta marineros y cien infantes de marina y precedidos por la brigada del general Fane que constaba de los regimientos 4º y 10º de la caballería portuguesa y el 5º de Caçadores, en total, unos 1.500 efectivos.

La noche del 11 al 12 de noviembre los artilleros portugueses y Lindsay emplazaron la batería de cohetes, y la mañana siguiente dispararon a una serie de embarcaciones que se hallaban en la orilla opuesta del Tajo, con poco efecto y los franceses se limitaron a quitarlas de en medio. Se ordenó a Lindsay que enviara a Salvatierra todos los cohetes, excepto 48 unidades de 32 libras y 144 unidades de 12 libras que eran los que cabían en dos carros de bueyes. Tras pasar 4 días inactivo, de repente Fane ordenó desplazar los cohetes restantes e incendiar la parte baja de la ciudad, ya que se había recibido información que los franceses habían concentrado en ella un depósito de carromatos y embarcaciones. Lindsay objetó que 48 cohetes eran insuficientes para incendiar una ciudad con edificios aislados entre sí, construidos en piedra completamente despojado de muebles por los habitantes. A pesar de todo:

«Me vi obligado a obedecer y, en consecuencia, tomé posición a unas 1600 metros de la ciudad. El primer cohete entró en medio de la ciudad y el segundo incendió una casa, pero al no tocar los cañones en el lugar, como yo había pedido, el enemigo lo apagó pronto, el resto de los cohetes fueron disparados sin producir ningún efecto visible, los alcances fueron uniformemente precisos. […] El Depósito pronto hizo su aparición siendo de una naturaleza tan móvil que salió de la ciudad antes de que hubiéramos terminado de disparar (aunque fuimos tan rápidos como nos fue posible) y resultó ser la munición y el equipaje de una División del Ejército Francés- ahora se comprobó que estaba en retirada.» [10]

De regreso a Almeirim, Wellington ordenaba a Fane que enviara de regreso uno de los carros de bueyes a Zamora y los caballos a Lisboa, por lo que Lindsay se encontró desprovisto de transportes y de oportunidades de poder demostrar el efecto de sus cohetes.

Although it may seem that the use of rockets was limited to the conflict in Central Europe, A. D. McCaig (see Sources) recounts the experiences of Lieutenant Lindsay and his Congreve rocket unit in Portugal in November 1810.

Lieutenant Lindsay had arrived in Portugal with a party of rockets and was at Zamora Borea (or Zamora Correia?) with his projectiles. Thinking he had enough mules for transportation, he had to make do with a few bullocks poles and reached his destination, Almeiria (Almeirim), about 6 kilometers from Santarem, on November 11, having stopped at Salvatiera (Salvatierra de Magos) and traveling at night to avoid enemy patrols. Lindsay was accompanied by a party of sixty sailors and one hundred marines, and preceded by General Fane’s brigade, consisting of the 4th and 10th regiments of Portuguese cavalry and the 5th Caçadores, a total of about 1,500 men.

On the night of November 11-12, the Portuguese artillerymen and Lindsay set up the rocket battery, and the next morning fired on a number of boats on the opposite bank of the Tagus, with little effect, and the French merely moved them out of the way. Lindsay was ordered to send all the rockets to Salvatierra, except 48 units of 32 pounds and 144 units of 12 pounds, which would fit in two bullocks carts. After 4 days of inactivity, Fane suddenly ordered the remaining rockets to be moved and the lower part of the town to be set on fire, as information had been received that the French had concentrated a depot of wagons and boats there. Lindsay objected that 48 rockets were not enough to set fire to a town with isolated buildings, built of stone and completely stripped of furniture by the inhabitants. In spite of everything:

«I was obliged to comply and accordingly took up position about 1800 Yards from the Town. The first Rocket went into the middle of the Town and the Second set a house on tire, but the guns not playing on the Spot, as I had requested they might, the enemy soon extinguished it, the remainder of the rockets were fired without producing any visible effect, the ranges were uniformly accurate. […] The Depot soon made irs appearance being of so moveable a nature that it bad letr the town before we had done firing (tho’ we were as quick as possible) and turned out to be the ammunition and baggage of a Division of the French Army- now ascertained to be on its retreat.» [10]

On his return to Almeirim, Wellington would order Fane to send back one of the bullock carts to Zamora and the horses to Lisbon, so Lindsay found himself bereft of transports and opportunities to be able to demonstrate the effect of his rockets.

En junio de 1812 tenemos constancia de la presencia de una fuerza unos 50 artilleros de la Royal Marine Artillery, al mando del teniente R. P. Campbell, que habían sido enviados a Sicilia (desde Cádiz) en junio de 1812 para ayudar en la dotación de los cañones de las cañoneras anglo-sicilianas. Curiosamente, estaban equipados con algunos de los cohetes de Congreve y 50 artilleros británicos y portugueses fueron asignados a esta Brigada de Cohetes. [6]

Durante el invierno de 1813 a 1814, también se estableció una pequeña brigada de cohetes que también estaba adscrita a una brigada de avanzada de la fuerza anglo-española a las afueras de Barcelona.

A pesar de la negativa visión de Wellington, éste permitió dos ensayos más de cohetes antes de pasar a la ofensiva en los Pirineos: uno en Urrugne (Francia) el 19 de enero de 1814, con resultados algo decepcionantes, y otro en Fuenterrabía (actual Hondarribia) el 10 de febrero de 1814 con mejores resultados, lo que dió ciertas esperanzas a sus partidarios para su uso futuro en la campaña.

Por tanto, volvemos a ver la presencia de los cohetes en Toulouse y en el paso del río Adour [3]. Esta última operación presentaba fuertes complicaciones: el Adour presentaba una gran anchura en su desembocadura, mareas y viento y la presencia de fuerzas francesas en la orilla norte y diversas cañoneras y una corbeta enemigas. Las tormentas retrasaron la operación de construcción de un puente hasta el 22 de febrero de 1814. Se habían emplazado cañones de 18 libras y una brigada de cohetes al mando del capitán Lane6. La 1ª División de infantería estaba en el punto de partida al amanecer del día 23 y los cañones estaban emplazados, pero no había ni rastro de las chasse-marées7 de la Royal Navy imprescindible para anclar los grupos de pontones. A pesar de todo se ordenó el despliegue de los pontones y 8 compañías avanzaron com la vanguardia, pero tan pronto como se descubrió el paso, dos mil soldados francese de Bayona, salieron decididamente para interceptar el paso, pero una descarga de cohetes – exitosa esta vez – hizo que los defensores volvieran a refugiarse entre los muros de la ciudad.

El oficial de los Guardias británicos, Rees Gronow, participó en esta acción y escribió sobre sus experiencias en sus memorias:

«La primera operación de nuestro cuerpo fue lanzar al 3º de Guardias… Sir John Hope ordenó a nuestra artillería, y cohetes… apoyar a nuestra pequeña banda. Tres o cuatro regimientos de infantería francesa se acercaban rápidamente, cuando un fuego bien dirigido de cohetes cayó entre ellos. La consternación de los franceses fue tal, cuando estos proyectiles sibilantes, como serpientes descendieron, que se produjo un pánico, y se retiraron sobre Bayona. Al día siguiente se terminó el puente de barcas y todo el ejército lo cruzó.» [10]

In June 1812 we have evidence of the presence of a force of about 50 gunners from the Royal Marine Artillery, under the command of Lieutenant R. P. Campbell, who had been sent to Sicily (from Cadiz) in June 1812 to assist in manning the guns of the Anglo-Sicilian gunboats. Interestingly, they were equipped with some of Congreve’s rockets and 50 British and Portuguese gunners were assigned to this Rocket Brigade. [6]

During the winter of 1813 to 1814, a small rocket brigade was also established which was also attached to an advance brigade of the Anglo-Spanish force outside Barcelona.

Despite Wellington’s negative view, he allowed two more rocket trials before going on the offensive in the Pyrenees: one at Urrugne (France) on January 19, 1814, with somewhat disappointing results, and another at Fuenterrabía (present-day Hondarribia) on February 10, 1814 with better results, which gave some hope for their future use in the campaign.

We therefore see again at the presence of rockets in Toulouse and at the Adour river crossing [3]. The latter operation presented serious complications: the Adour was very wide at its mouth, tides and wind, and the presence of French forces on the north bank and several enemy gunboats and a corvette. Storms delayed the pontoon-building operation until 22 February 1814. Eighteen-pounder guns and a rocket brigade under Captain Lane6 had been emplaced. The 1st Infantry Division was at the starting point at dawn on the 23rd and the guns were emplaced, but there was no sign of the Royal Navy chasse-marées7 needed to anchor the pontoon groups. The pontoons were nevertheless ordered to deploy and 8 companies advanced as the vanguard, but as soon as the passage was discovered, two thousand French soldiers from Bayonne set off resolutely to intercept the passage, but a volley of rockets – successful this time – drove the defenders back into the city walls.

British Guards officer Rees Gronow took part in the latter action and wrote about his experiences in his memoirs:

«The first operation of our corps was to throw over the 3rd Guards… Sir John Hope ordered our artillery, and rockets… to support our small band. Three or four regiments of French infantry were approaching rapidly, when a well-directed fire of rockets fell amongst them. The consternation of the Frenchmen was such, when these hissing, serpent-like projectiles descended, that a panic ensued, and they retreated upon Bayonne. The next day the bridge of boats was completed, and the whole army crossed.» [10]

Por último, en la batalla de Toulouse, el 10 de abril de 1814, que sería la última batalla de la campaña, una compañía de la Tropa de Cohetes en el contingente de Beresford (que se hallaba sin artillería) se situó en batería y disparó sus proyectiles sobre el reducto de La Sypière en el ataque efectuado por la división de Cole. Los reclutas franceses, que no habían visto nunca dicha arma, desalojaron el reducto.

Finally, at the Battle of Toulouse on 10 April 1814, which was to be the last battle of the campaign, a company of the Rocket Troop in Beresford’s contingent (which was without artillery) took up a battery position and fired its shells on the redoubt of La Sypière in the attack by Cole’s division. The French recruits, who had never seen such a weapon, cleared the redoubt.

WELLINGTON Y EL USO DE LOS COHETES / WELLINGTON AND THE USE OF ROCKETS

Arthur Welleslley (futuro Lord Wellington), un comandante en jefe pragmatico como pocos, no puede decirse que fuera muy partidario de la utilización de un arma novedosa como los cohetes Congreve en el campo de batalla. Los había contemplado en la India pero las primeras experiencias en Woolwich habían sido desiguales y solo el apoyo real había permitido seguir con los experimentos. Como comenta Nick Lipscombe sobre Wellington (ver Fuentes), “sus relaciones personales con sus comandantes de artillería se vieron ensombrecidas por su actitud autocrática y dictatorial y su incapacidad para soportar gustosamente a los tontos, mientras que su trato hacia ciertos individuos, concretamente Norman Ramsay ejemplifica que era un amo ingrato al que servir.”

Como los cohetes no dejaban de ser una unidad o Tropa adscrita al arma de artillería y Wellington se ceñía a un orden concreto en sus tácticas lineales de batalla, quizás el comportamiento a menudo errático de los cohetes no encajaba adecuadamente en tales esquemas, agravado por las opinions de los afines al comandante en jefe. Dixon, su comandante de artillería más afin, no tenía buena opinion de los cohetes Congreve4 y otros como Cavalié Mercer que participó en Waterloo, no dejaron de comentar negativamente sus experiencias: “soltaron los cohetes y se elevaron en el aire retorciéndose y algunos de ellos luego giraron sobre nosotros y volvieron en todas direcciones, nos pusieron bajo más peligro ese día que cualquier francés”.

A pesar de tales opiniones, Wellington parece que no puso impedimentos a que una unidad de cohetes desembarcara en Portugal y que se experimentase su aplicación de una manera más directa5. Una vez la campaña llegó a tierras pirenaicas en Francia, los cohetes fueron empleados en el paso del rio Adour con más éxito.

En 1815, Edward C. Whinyates, al mando de la 2ª tropa de cohetes, tenía su batería de cohetes en Bélgica y Wellington cuando estaba inspeccionando la artillería con el mariscal Blücher alrededor de un mes antes de Waterloo, al norte de Bruselas, se encontró con esta batería de cohetes y se dio la vuelta al coronel George Wood. El diálogo fue algo como «Bueno eso era la batería de cohetes, señor, usted sabe que estos cohetes participaron en Leipzig», y él dijo: «No me importa lo que hicieron en Leipzig, no quiero cohetes». [11]

Pero los cohetes estuvieron en Waterloo, por lo que si bien la desconfianza de Wellington era manifiesta, como buen pragmático, no perdería la oportunidad de utilizar un arma que le diera alguna ventaja significativa en el campo de batalla (u obviar su presencia mientras no le representara un problema).

Arthur Welleslley (future Lord Wellington), a pragmatic commander-in-chief like few others, could not be said to be a great believer in the use of a novel weapon such as Congreve rockets on the battlefield. He had contemplated them in India but early experiences at Woolwich had been mixed and only Royal support had allowed the experiments to continue. As Nick Lipscombe states about Wellington’s gunners (see Sources), «his personal relations with his gunnery commanders were overshadowed by his autocratic and dictatorial attitude and his inability to bear fools gladly, while his treatment of certain individuals, namely Norman Ramsay exemplified that he was an ungrateful master to serve».

As the Rockets were still a unit or troop attached to the artillery, and Wellington adhered to a particular order in his linear tactics of battle, perhaps the often erratic behaviour of the Rockets did not fit neatly into such schemes, compounded by the opinions of those sympathetic to the commander-in-chief. Dixon, his most like-minded artillery commander, did not think highly of the Congreve rockets4, and others, such as Cavalié Mercer who took part in Waterloo, did not fail to comment negatively on his experiences: «they let the rockets loose and they went up in the air twisting and turning and some of them then turned on us and came back in all directions, they put us in more danger that day than any Frenchman».

Despite such views, Wellington seems to have put no obstacles in the way of a rocket unit landing in Portugal and experimenting with their application in a more direct way.5 Once the campaign reached the Pyrenees in France, rockets were employed in the Adour Pass with more success.

In 1815, Edward C. Whinyates, commanding the 2nd Rocket Troop, had his rocket battery in Belgium and Wellington when he was inspecting the artillery with Marshal Blücher about a month before Waterloo, north of Brussels, came across this rocket battery and turned to Colonel George Wood. The dialogue was something like «Well that was the rocket battery, sir, you know these rockets were involved at Leipzig,» and he said, «I don’t care what they did at Leipzig, I don’t want rockets.» [11]

But the rockets were at Waterloo, so while Wellington’s distrust was manifest, as a good pragmatist, he would not miss an opportunity to use a weapon that would give him some significant advantage on the battlefield (or to ignore its presence as long as it was not a problem).

1Para desarrollar su sistema, Congreve se apoyó en un poderoso mecenazgo. Congreve era conocido del príncipe de Gales, más tarde Jorge IV, y a menudo le presentaba proyectos en Carlton House, en Pall Mall, o en el arquetípico lugar orientalista de principios del siglo XIX, el Marine o Royal Pavilion de Brighton. En el pabellón, Congreve mostraba al príncipe planos para imitar cohetes indios y utilizó el patrocinio del príncipe para «pasar por encima» de la oposición. Después de que George ordenara a William Pitt prestar «atención inmediata a la adopción del cohete» el Primer Ministro se dirigió a Robert Stewart, vizconde de Castlereagh, su ministro de Guerra, para que organizara pruebas en el mar. [5] Ni qué decir que tales relaciones le despertarían no pocos recelos y envidias entre sus contemporáneos y en el ejército.

2El poco número de cohetes sin embargo fue suficiente como para que algunos de ellos no explotaran, lo que significó que el subteniente danés Schumacher encontrara uno o dos de ellos intactos y, después de un par de años, tratara de aprender los rudimentos del artilugio de William Congreve fabricando los cohetes él mismo. [7]

3Una parte de la brigada de cohetes ya había participado en la batalla de Göhrde el 16 de septiembre de 1813, formando parte de la Legión Alemana del Rey. De mayor importancia fue la «Batalla de las Naciones» en Leipzig, que tuvo lugar del 16 al 19 de octubre de 1813, en la que la Tropa de cohetes fue la única representante del Ejército Británico, encuadrada en el «Ejército del Norte» bajo el mando de Bernadotte, príncipe heredero de Suecia. Lamentablemente, el capitán Bogue al mando de la unidad murió de un balazo en la cabeza, pero la tropa recibió honores del comandante sueco y del emperador de Rusia y el Príncipe Regente en Inglaterra les concedió el honor de batalla «Leipzig».

4 [Dixon] pensaba que: «su Señoría piensa de manera muy barata de los cohetes, derivando su conocimiento de ellos probablemente del uso que se hace de ellos en la India». [6]

5Congreve había escrito al coronel Bunbury el 4 de diciembre de 1810: «Tengo el placer de adjuntarle una carta del Teniente Lindsay, por la que tendrá la satisfacción de saber que sus servicios han sido requeridos inmediatamente por lord Wellington». [10] (¿Presiones desde el gobierno británico?)

6El capitán Lane, de la Artillería, había llegado al puerto de Pasages, con un destacamento de cohetes de cincuenta hombres, pero sin caballos. Lord Wellington había permitido que se probara una división de cohetes. La división significa dos carros de cohetes, de los cuales cada carro transporta unos cincuenta cohetes, y habrá un par de carros en reserva. Los caballos previstos por Dixon (44 animales) fueron destinados por Wellington para llevar el tren de pontones para cruzar el Adour, por lo que significó un desafío logístico para el eficiente comandante de artillería británico el poder llevar los cohetes a su destino. [6]

7En inglés, un chasse-marée es un tipo específico y arcaico de velero comercial con cubierta.

1Congreve relied on powerful patronage to develop his system. Congreve was an acquaintance of the Prince of Wales, later George IV, and often presented projects to him at Carlton House, on Pall Mall, or at the archetypal early nineteenth-century Orientalist venue, the Marine or Royal Pavilion in Brighton. At the pavilion, Congreve showed the prince plans for imitation Indian rockets and used the prince’s patronage to ‘ride roughshod’ over opposition. After George ordered William Pitt to give «immediate attention to the adoption of the rocket» the Prime Minister turned to Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh, his Minister of War, to organise sea trials. [5] Needless to say, such dealings would arouse no small amount of suspicion and envy among his contemporaries and in the Army.

2The small number of rockets, however, was sufficient for some of them not to explode, which meant that Danish second lieutenant Schumacher found one or two of them intact and, after a couple of years, tried to learn the rudiments of William Congreve’s contraption by making the rockets himself. [7]

3A part of the rocket brigade had already taken part in the Battle of Göhrde on 16 September 1813, forming part of the King’s German Legion. Of greater importance was the «Battle of the Nations» at Leipzig, which took place from 16-19 October 1813, in which the Rocket Troop was the only representative of the British Army, as part of the «Army of the North» under the command of Bernadotte, Crown Prince of Sweden. Unfortunately, Captain Bogue commanding the unit was killed by a bullet to the head, but the troop received honours from the Swedish commander and the Emperor of Russia and was awarded the battle honour «Leipzig» by the Prince Regent in England.

4[Dixon] thought: «his Lordship thinks very cheaply of rockets, deriving his knowledge of them probably from the use that is made of them from India» [6]

5Congreve had written to Colonel Bunbury on 4 December 1810: «I have the pleasure to inclose to you a letter from Lieutenant Lindsay, by which you will have the satisfaction to find that his services have been immediately called for by Lord Wellington.» [10] (Pressure from the British government?)

6Captain Lane, of the Royal Artillery, had arrived in the port of Pasages, with a rocket detachment of fifty men, but without horses. Lord Wellington had allowed a division of rockets to be tried out. The division meant two rocket waggons, of which each wagon carried about fifty rockets, and with a couple of waggons in reserve. The horses envisaged by Dixon (44 animals) were intended by Wellingotn to carry the pontoon train across the Adour, making it a logistical challenge for the efficient British artillery commander to get the rockets to their destination. [6]

7In English, a chasse-marée is a specific and archaic type of decked commercial sailing vessel.

Fuentes:

1 – “British Napoleonic Field Artillery” – The first complete illustrated guide to equipment and uniforms” – CE.Franklin, Spellmount, Great Britain, 2008

2 – «The Rocket Brigade in early 19th Century» – W. Y. Carman, Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, Vol. 41, No. 168 (December, 1963), pp. 167-170

3 – «The use of war rockets in the British army in the nineteenth century» – G. Tylden, Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, Vol. 26, No. 108 (Winter, 1948), pp. 168-170

4 – «The Details of the Rocket System Employed by the British Army During the Napoleonic Wars» – William Congreve, LEONAUR (17 mayo 2021)

5 – «William congreve’s rational rockets» – Simon Werrett, Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London, Vol. 63, No. 1 (20 March 2009), pp. 35-56

6 – «Wellington’s Guns: The Untold Story of Wellington and his Artillery in the Peninsula and at Waterloo» – Nick Lipscombe, Osprey Publishing Ltd. Edición de Kindle, 2013.

7 – https://www.rundetaarn.dk/en/article/rocket-science-seen-from-the-round-tower/

8 – «British Rockets of the Napoleonic and Colonial Wars 1805-1901» – C. E. Franklin, Spellmount, Great Britain, 2005

9 – https://kidskonnect.com/people/sir-william-congreve

10 – «The Soul of artillery: Congreve’s rockets and their effectiveness in warfare» – A.D. Mc Caig, Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research 78 (2000), 252-26

11 – «Wellington in Spain. A Classic Peninsular War Tour». 12 a 19/09/2018 – Nick Lipscombe©, para «The Cultural Experience».

12 – https://ageofrevolution.org/200-object/congreve-rocket/

13 – https://collections.spacecentre.co.uk/object-l2010-4

14 – «Historia de las comunicaciones. Transportes Aéreos» – Valery Bridges, Salvat SA de Ediciones, Estella (Navarra), 1968

15 – «The details of the Rocket System: shewing the various applications of this weapon, both for sea and land service, and its different uses in the field and in sieges», London, 1814

16 – «Toulouse 1814. La última batalla de la Guerra de Independencia Española» – Francisco Vela Santiago, Editorial Almena, Madrid, 2014

Imágenes:

a – Captura de pantalla juego PC «Napoleón Total War: Definitive Edition» – 01/05/2024 _ 13:02 PM

b – Foto del autor.

c – «The details of the Rocket System: shewing the various applications of this weapon, both for sea and land service, and its different uses in the field and in sieges», London, 1814

d – By James Lonsdale – one or more third parties have made copyright claims against Wikimedia Commons in relation to the work from which this is sourced or a purely mechanical reproduction thereof. This may be due to recognition of the «sweat of the brow» doctrine, allowing works to be eligible for protection through skill and labour, and not purely by originality as is the case in the United States (where this website is hosted). These claims may or may not be valid in all jurisdictions.As such, use of this image in the jurisdiction of the claimant or other countries may be regarded as copyright infringement. Please see Commons:When to use the PD-Art tag for more information., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6365161

e – «Historia de las comunicaciones. Transportes Aéreos» – Valery Bridges, Salvat SA de Ediciones, Estella (Navarra), 1968

f – «The details of the Rocket System: shewing the various applications of this weapon, both for sea and land service, and its different uses in the field and in sieges», London, 1814

g – «A pictural plan of the present position of the French army at Santarem in Portugal march 1811 from the british advanced post in front of Valle» published 25 mar 1811 / https://col.rct.uk/sites/default/files/collection-online/6/1/677753-1491392840.jpg

h – Foto del autor.

i – ©National Portrait Gallery, London. Used by permission to use solely according personal licence, detailed at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

j – https://ageofrevolution.org/200-object/congreve-rocket/

k – https://maisonmilitaire.com/product/nap0528-british-congreve-rocket-system/?v=04c19fa1e772

BRAVO! Genial!!!

Me gustaMe gusta

Gracias por el comentario. Si ha gustado ya ha cumplido su objetivo.

Me gustaMe gusta