Tiempo de lectura: 22 minutos

Os traemos esta semana un artículo sobre la transmisión de información mediante la telegrafía óptica en Portugal durante la Guerra de Independencia, en una exposición permanente que se encuentra en el Museu Militar de Elvas, en Portugal. La transmisión de mensajes entre dos puntos distantes siempre ha sido una cuestión de importancia para un ejército de un país, buscando siempre la transmisión a más distancia y con la mayor información posible, desde los primeros correos o mensajeros a pie (recordemos al griego Filípides en tiempos de la Gracia clásica) o a caballo, individualmente o más modernamente en el tiempo, por relevos de postas.

Pero el envío de información por estos medios se vio superado en el tiempo por la transmisión de señales desde puntos altos sobre el terreno, desde colinas naturales del mismo o sobre construcciones artificiales hechas por el hombre (atalayas, torres de vigía, almenaras, etc.). Estas señales se transmitieron en sus inicios mediante el empleo del fuego o utilizando banderas de señales (como en la marina de guerra), o ya desde finales del s.XVIII con el uso de artilugios mecanizados con los que poder elaborar un código de señales, que pudiera transmitir mensajes más elaborados y a más distancia. El francés Claude Chappe (1763-1805) fue uno de los pioneros en este tipo de transmisiones, elaborando un sistema de transmisiones mediante el empleo de unos mástiles unidos entre sí y manejados con poleas cuya variación de orientación formaba una combinación de un código previamente escrito. En España tuvimos precursores de dicha tecnología como Josep Fornell, Agustín de Betancourt o el teniente coronel de ingenieros Francisco Hurtado.

Posteriormente, en el frente oeste de la Península, habiéndose retirado Wellington a las recién construidas Líneas de Torres Vedras durante la 3ª invasión de Portugal, el poder transmitir la información entre los diferentes reductos o fortines de las líneas de defensa se convirtió en una acuciante necesidad, por lo que se implantaron sistemas de comunicaciones con instrumentales ópticos, primero de procedencia inglesa con sus sistemas de bolas, que se solaparían posteriormente con artilugios de construcción portuguesa nacional, en dos prototipos obra del matemático y astrónomo Francisco Antonio Ciera, que desarrolló todo un sistema de señales y un completo vocabulario de transmisiones, que facilitaba el envío y recepción de información a través de la distancia.

This week we bring you an article on the transmission of information by optical telegraphy in Portugal during the Peninsular War, in a permanent exhibition at the Military Museum in Elvas, Portugal. The transmission of messages between two distant points has always been a matter of importance for a country’s army, which has always sought to transmit messages over the greatest possible distance and with as much information as possible, from the first couriers or messengers on foot (remember Philippides in classical Greek times) or on horseback, individually or, more recently, by relay.

However, sending information by these means was eventually superseded by the transmission of signals from high points on the ground, from natural hills or man-made structures (watchtowers, beacons, lighthouses, etc.). These signals were initially transmitted by means of fire or signal flags (as in the navy), or, from the end of the 18th century, by means of mechanised devices with which to develop a code of signals that could transmit more elaborate messages over greater distances. The Frenchman Claude Chappe (1763-1805) was one of the pioneers in this type of transmission, developing a transmission system using masts joined together and operated by pulleys, whose variation in orientation formed a combination of a previously written code. In Spain, we had precursors of this technology such as Josep Fornell, Agustín de Betancourt and Lieutenant Colonel Francisco Hurtado of the Engineers.

Later, on the western front of the Peninsula, after Wellington had retreated to the newly built Lines of Torres Vedras during the third invasion of Portugal, the ability to transmit information between the different strongholds or forts of the defence lines became a pressing need, so communications systems were implemented using optical instruments, first from England with their ball systems, which would later be replaced by Portuguese-made devices, in two prototypes designed by mathematician and astronomer Francisco Antonio Ciera, who developed a whole system of signals and a complete vocabulary of transmissions, which facilitated the sending and receiving of information over long distances.

LOS COMIENZOS DE LAS COMUNICACIONES

En franco contraste con estas grandes transformaciones que se comprobaban en el país, las comunicaciones, durante este período de casi setecientos años, no tuvieron una evolución significativa, a semejanza de lo que ocurría en todo el mundo. Durante este largo período no hubo ninguna innovación en las comunicaciones terrestres. En efecto, solo se utilizaron medios sonoros, medios visuales (humo, fuego, banderas), y mensajeros que podían desplazarse a pie o a caballo.

Montados a caballo, podemos considerar que los mensajeros constituyeron siempre un medio de transporte de información a través de todas las épocas. En la actualidad se utiliza no solo en pequeñas distancias, pero también en grandes distancias, en particular en el transporte de información de la más alta clasificación de seguridad (TOP SECRET).

THE DAWNING OF COMMUNICATION

In stark contrast to these major transformations taking place in the country, communications during this period of almost seven hundred years did not undergo any significant evolution, similar to what was happening throughout the world. During this long period, there were no innovations in land-based communications. In fact, only sound and visual means (smoke, fire, flags) and messengers who could travel on foot or on horseback were used.

On horseback, messengers can be considered to have always been a means of transporting information throughout the ages. Today, they are used not only for short distances but also for long distances, particularly for transporting information of the highest security classification (TOP SECRET).

TORRES DE VIGÍA / WATCHTOWERS

Las torres de vigía eran pequeñas construcciones localizadas en puntos estratégicos del terreno (normalmente elevaciones o lugares de control en los cursos de agua), que permitían la observación a distancia de la aproximación de grupos o fuerzas enemigas.

Watchtowers were small structures located at strategic points on the terrain (usually elevations or control points on watercourses), which allowed distant observation of approaching enemy groups or forces.

ALMENARAS / BEACONS

Las almenaras eran estructuras en forma de torre y localizadas en puntos altos del terreno, en las que en su parte superior se encendían hogueras para utilizar el humo durante el día o durante la noche utilizar la luz, con la finalidad de transmitir información de una manera simple sobre la presencia de fuerzas enemigas.

Beacons were tower-shaped structures located on high points of land, at the top of which bonfires were lit to use the smoke during the day or the light at night, with the aim of transmitting information in a simple way about the presence of enemy forces.

A finales del siglo XVIII se inició en Francia un sistema de telegrafía visual terrestre que utilizando señales ópticas transmitidas entre varias estaciones -colocadas a lo largo de un determinado recorrido e interpretado en una lista de códigos previamente elaborada- permitió transmitir mensajes a grandes distancias.

De todos los iniciativas emprendidas para crear un sistema rápido y eficiente de telegrafía visual, fue la del francés Claude Chappe la que obtuvo mayor éxito y llevó a la creación del telégrafo con su nombre, que adquirió gran proyección y dio lugar a la aparición, pocos años después, de otras versiones de telégrafos en otros países entre los que destacan las del sueco Edelcrantz y el inglés Murray.

At the end of the 18th century, a terrestrial visual telegraphy system was launched in France. Using optical signals transmitted between several stations—placed along a specific route and interpreted using a previously prepared list of codes—it enabled messages to be transmitted over long distances.

Of all the initiatives undertaken to create a fast and efficient visual telegraph system, it was that of the Frenchman Claude Chappe that was most successful and led to the creation of the telegraph bearing his name, which became widely known and gave rise, a few years later, to other versions of telegraphs in other countries, notably those of the Swede Edelcrantz and the Englishman Murray.

A la izquierda grabado mostrando un telégrafo francés de Chappe que tiene el nombre de su inventor. Fue el primer telégrafo óptico (1795), a partir del cual se inició la transmisión a distancia de mensajes.

On the left is an engraving showing a French telegraph by Chappe, named after its inventor. It was the first optical telegraph (1795), which marked the beginning of long-distance message transmission.

LA GUERRA PENINSULAR

A partir de su llegada al poder en Francia, Napoleón Bonaparte inicia la conquista imperial de Europa, y en su plan estratégico de ocupación progresiva, la conquista de la Península Ibérica estaba, naturalmente, incluida.

A pesar de una actividad política y diplomática frenética con el fin de mantener la neutralidad, el Estado portugués acabó por aliarse del lado de Inglaterra, ya con el rey Joao VI refugiado con su corte en Brasil, comenzando el periodo llamado Guerra Peninsular.

Las tropas francesas, comandadas por el general Junot, entraron en la frontera de Portugal, en noviembre de 1807, dando comienzo a la primera de las tres invasiones francesas. El ejército anglo-luso combatió al invasor con la masiva participación de la guerrilla popular, acabando por alcanzar la derrota definitiva de los franceses en 1814.

THE PENINSULAR WAR

Upon coming to power in France, Napoleon Bonaparte began his imperial conquest of Europe, and his strategic plan for progressive occupation naturally included the conquest of the Iberian Peninsula.

Despite frenetic political and diplomatic activity aimed at maintaining neutrality, the Portuguese state ended up allying itself with England, with King João VI and his court taking refuge in Brazil, thus beginning the period known as the Peninsular War.

French troops, commanded by General Junot, entered the Portuguese border in November 1807, marking the beginning of the first of three French invasions. The Anglo-Portuguese army fought the invaders with the massive participation of popular guerrilla forces, ultimately achieving the definitive defeat of the French in 1814.

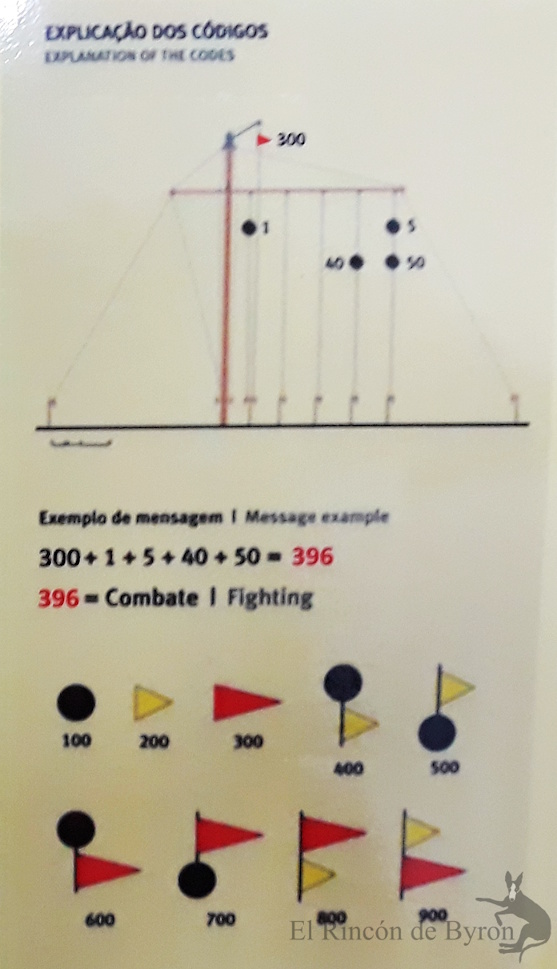

EL TELÉGRAFO DE BOLAS

Conocido también por el telégrafo inglés, ya que era el modelo que los británicos llevaron a Portugal con el fin de apoyar a ciertos dispositivos operativos diseñados para combatir las invasiones francesas. Se utilizaron principalmente en las Líneas de Torres Vedras, durante la 3ª invasión francesa.

Su funcionamiento es también por códigos que se corresponden con diferentes combinaciones que se pueden formar con las posiciones de las bolas.

THE BALL TELEGRAPH

Also known as the English telegraph, as it was the model that the British brought to Portugal to support certain operational devices designed to combat French invasions. They were mainly used on the Lines of Torres Vedras during the third French invasion.

It also works using codes that correspond to different combinations that can be formed with the positions of the balls.

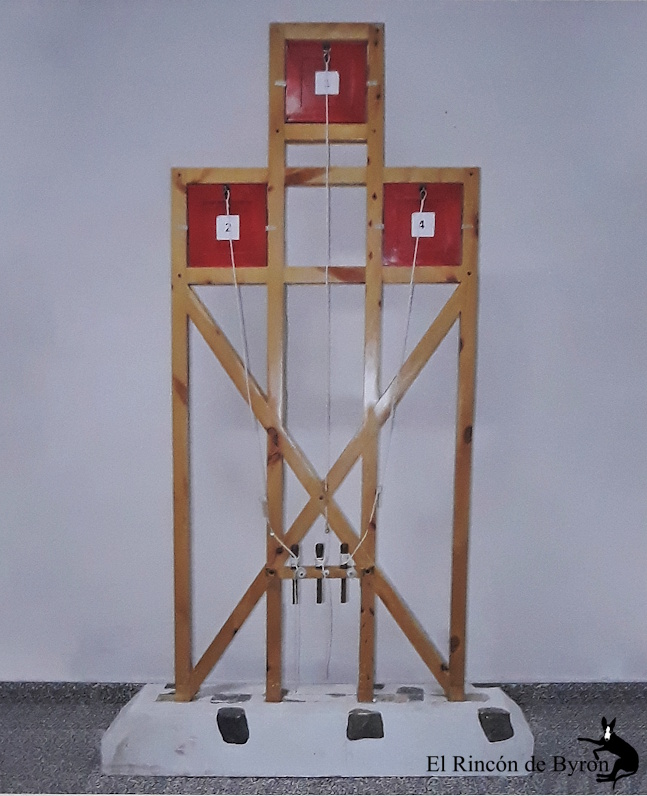

Maqueta del telégrafo de bolas utilizado en las líneas de Torres Vedras (1810)

Model of the ball telegraph used on the Torres Vedras lines (1810)

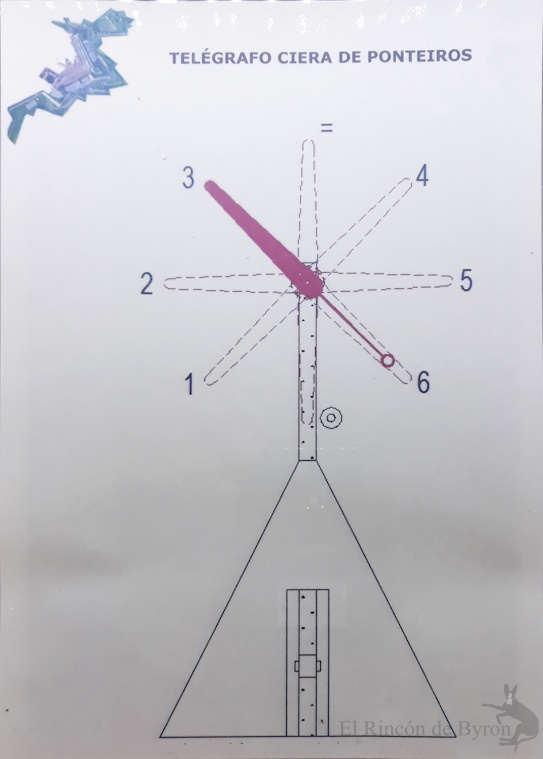

TELÉGRAFO CIERA DE PUNTERO

Fue el primer telégrafo visual terrestre portugués, inventado, desarrollado y construido por Francisco Antonio Ciera* Con base en este aparato, se establecieron diversas redes telegráficas por todo el país. Generalmente su funcionamiento se basa en 8 posiciones del puntero (2 en el eje vertical, 2 en el eje horizontal y 2 en cada una de las dos bisectrices a 45º), correspondiendo a cada uno un código, que se descodifica en tablas previamente preparadas.

En cuanto a su funcionamiento, Francisco Ciera escribe:

«A primera vista parece imposible satisfacer todo solamente con 8 señales; conseguí esto por medio de un diccionario que compuse y que contiene más de 60.000 palabras y frases, cada una de las cuales tiene por expresión telegráfica, una combinación de los números 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 y 6, tomados, a dos, a cuatro, a cinco, a seis.«

CIERA DE PUNTERO TELEGRAPH

It was the first Portuguese terrestrial visual telegraph, invented, developed and built by Francisco Antonio Ciera*. Based on this device, various telegraph networks were established throughout the country. Its operation is generally based on eight pointer positions (two on the vertical axis, two on the horizontal axis and two on each of the two 45° bisectors), each corresponding to a code that is decoded using pre-prepared tables.

Regarding its operation, Francisco Ciera writes:

«At first glance, it seems impossible to convey everything with only 8 signals; I achieved this by means of a dictionary that I compiled, containing more than 60,000 words and phrases, each of which has a telegraphic expression consisting of a combination of the numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6, taken in groups of two, four, five and six.«

Frente a su ventaja desde el punto de vista de la instalación y de la maniobrabilidad, sobre todo en campaña, el punto débil del telégrafo de puntero era su alcance o visibilidad: mientras que éste, según su propio autor, no debía llegar a superar las 2,5 leguas (siempre en función de las dimensiones de la flecha), el telégrafo de persianas permitía alcanzar entre las 3 y las 6 leguas (1 legua UK= 4830.91 m).

Despite its advantages in terms of installation and manoeuvrability, especially in the field, the weak point of the pointer telegraph was its range or visibility: while the latter, according to its own inventor, should not exceed 2.5 leagues (depending on the dimensions of the arrow), the shutter telegraph could reach between 3 and 6 leagues (1 UK league = 4830.91 m).

Carta de Francisco Antonio Ciera sobre dos soldados incapacitados para el servicio telegráfico, fechada en Lisboa, el 11 de marzo de 1806.

Letter from Francisco Antonio Ciera regarding two soldiers unfit for telegraph service, dated in Lisbon, 11 March 1806.

MANIQUÍ VESTIDO DE ÉPOCA JUNTO A LOS TELÉGRAFOS / MANNEQUIN WEARING PERIOD DRESS NEXT TO THE TELEGRAPHS

En las diferentes estaciones de la red telegráfica, cada telégrafo tenía un operador, que con la mano izquierda giraba el puntero a la posición deseada; con el ojo izquierdo acechaba por el monóculo hacia la estación que enviaba la señal, y con la mano derecha escribía sobre una pizarra colocada en una posición adecuada sobre el mástil.

Descripción escrita por el propio Francisco Antonio Ciera:

«El sistema portugués (que se propuso después de considerar los otros muchos presentados) tiene una sola manivela, con la cual se da a su único puntero las inclinaciones de 45º en 45º con respecto al mástil vertical; de suerte que un solo hombre observa, hace las señales y escribe, todo a un tiempo; porque tiene la vista aplicada a una luneta fija al mástil, mueve la manivela con la mano izquierda, quedando la derecha libre para poder escribir en una pizarra convenientemente aplicada al mástil para ese fin».

At the different stations of the telegraph network, each telegraph had an operator, who used his left hand to turn the pointer to the desired position; with his left eye, he looked through the monocular towards the station sending the signal, and with his right hand, he wrote on a slate placed in a suitable position on the mast.

Description written by Francisco Antonio Ciera himself:

«The Portuguese system (which was proposed after considering the many others presented) has a single crank, with which its single pointer is tilted at 45º intervals with respect to the vertical mast; so that a single man observes, makes the signals and writes, all at the same time; because he has his eyes fixed on a telescope attached to the mast, he moves the crank with his left hand, leaving his right hand free to write on a slate conveniently attached to the mast for that purpose.«

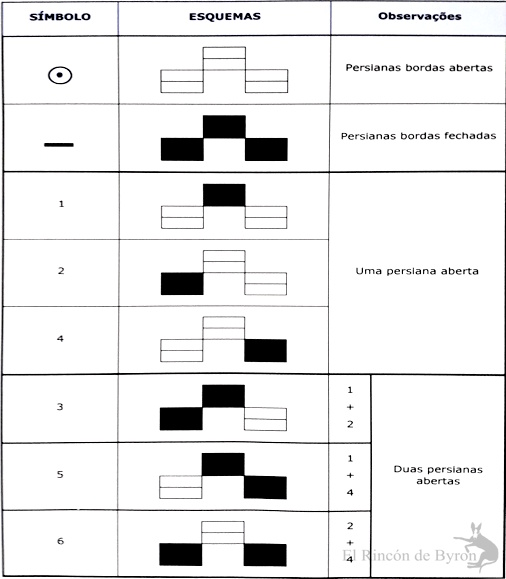

TELÉGRAFO CIERA DE PERSIANAS / CIERA’S SHUTTER TELEGRAPH

Las 8 posiciones del telégrafo de persianas se replican en una combinación de apertura y cierre de las 3 persianas. Las tablas de decodificación son las mismas. Tiene la ventaja de permitir una construcción de mayor volumen y, por lo tanto, permitir mayores alcances.

Las persianas tienen las siguientes posiciones:

– Persianas bordes abiertos

– Persianas bordes cerrados

– Una persiana abierta

– Dos persianas abiertas

El cuadro inferior permite observar cómo se hacía la combinación de la apertura y cierre de las persianas para poder transmitir números de 0 a 6. Las tablas se construyeron sobre la base de estos números.

The 8 positions of the shutter telegraph are replicated in a combination of opening and closing the 3 shutters. The decoding tables are the same. It has the advantage of allowing for a larger volume construction and, therefore, greater ranges.

The shutters have the following positions:

– Shutters with open edges

– Shutters with closed edges

– One shutter open

– Two shutters open

The table below shows how the combination of opening and closing the shutters was done in order to transmit numbers from 0 to 6. The tables were constructed on the basis of these numbers.

LA TELEGRAFÍA ÓPTICA Y EL CUERPO TELEGRÁFICO / OPTICAL TELEGRAPHY AND THE TELEGRAPHIC CORPS

Durante la Guerra de la Independencia, las comunicaciones juegan un papel importante en las líneas de Torres Vedras para permitir, mediante la telegrafía óptica, el contacto entre los principales fortines de la posición defensiva portuguesa. Se utilizaron inicialmente telégrafos ópticos de bolas, utilizados por la marina inglesa. Estas conexiones fueron progresivamente establecidas, solapadamente, con telégrafos de concepción portuguesa nacional, para así garantizar la existencia de medios alternativos. Es importante señalar, en este momento, que los telégrafos de concepción nacional tuvieron su origen en la siguiente circunstancia:

En Portugal, en los primeros años del siglo XIX, la marina portuguesa tenía ya en funcionamiento una línea de telégrafos visuales llamada Línea de Barra, entre el Cabo da Roca y el Castillo de San Jorge, con varias estaciones intermedias que permitían el control militar y aduanero del puerto de Lisboa y la comunicación entre los buques y tierra. Los telégrafos utilizados eran llamados semáforos y estaban constituidos por un mástil (como sucedía en los barcos) con banderas y balones, que combinados entre sí formaban señales, que eran interpretadas utilizando listas de códigos. Fue el estudio de estos sistemas telegráficos visuales terrestres que permitió a Francisco Antonio Ciera crear, desarrollar e implementar el telégrafo visual terrestre portugués, que cambiaría por completo el panorama de las comunicaciones en Portugal durante varios decenios.

Fue este telégrafo el que en las Líneas de Torres Vedras constituyó la alternativa al telégrafo de bolas traído por los ingleses. En 1810 se creó el Cuerpo Telegráfico**, que constituyó la primera unidad de Transmisiones Permanentes, siendo su primer comandante Francisco Ciera, un civil, perteneciente a la Universidad de Coimbra e inventor del telégrafo óptico portugués. Con este telégrafo, se establecieron en el país varias redes militares de telegrafía, que sirvieron para apoyar a la administración del reino. En esta red no fue prevista la posibilidad de su utilización futura por el público en general.

During the Peninsular War, communications played an important role in the Torres Vedras lines, enabling contact between the main forts of the Portuguese defensive position through optical telegraphy. Initially, ball optical telegraphs, used by the British navy, were employed. These connections were gradually established, surreptitiously, with telegraphs of Portuguese national design, in order to guarantee the existence of alternative means. It is important to note, at this point, that the nationally designed telegraphs had their origin in the following circumstance:

In Portugal, in the early 19th century, the Portuguese navy already had a line of visual telegraphs in operation called the Barra Line, between Cabo da Roca and São Jorge Castle, with several intermediate stations that allowed military and customs control of the port of Lisbon and communication between ships and land. The telegraphs used were called semaphores and consisted of a mast (as on ships) with flags and balls, which were combined to form signals that were interpreted using code lists. It was the study of these visual terrestrial telegraph systems that enabled Francisco Antonio Ciera to create, develop and implement the Portuguese visual terrestrial telegraph, which would completely change the communications landscape in Portugal for several decades.

It was this telegraph that, in the Lines of Torres Vedras, provided an alternative to the ball telegraph brought by the English. In 1810, the Telegraph Corps was created, which was the first Permanent Transmissions unit, with its first commander being Francisco Ciera, a civilian belonging to the University of Coimbra and inventor of the Portuguese optical telegraph. With this telegraph, several military telegraph networks were established in the country, which served to support the administration of the kingdom. This network did not envisage the possibility of its future use by the general public.

Este telégrafo, visible en la parte superior de la Torre de Belén, era parte de la red de telégrafos visuales de la tierra, sirviendo a la ciudad de Lisboa en el primer cuarto del siglo XIX.

This telegraph, visible at the top of the Belém Tower, was part of the land-based visual telegraph network serving the city of Lisbon in the first quarter of the 19th century.

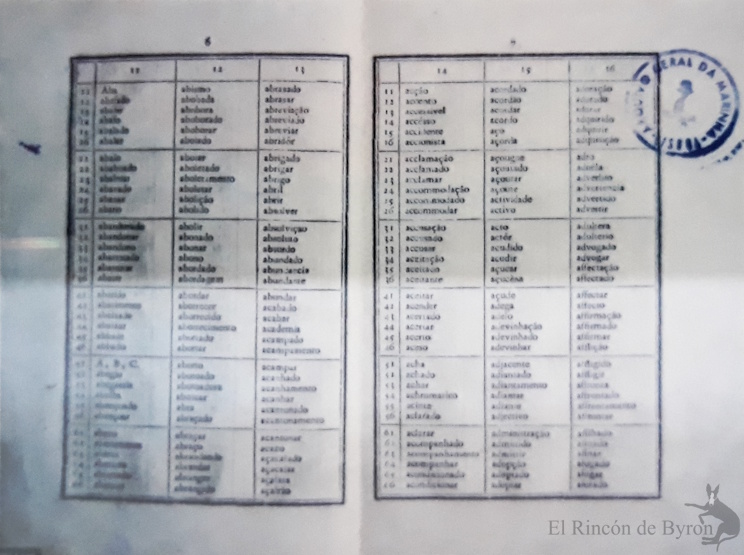

Portada de un libro de Tablas telegráficas, impreso en Lisboa en 1810. /Cover of a book of telegraphic tables, printed in Lisbon in 1810.

Cabe señalar que las tablas eran manuscritas y que sólo esta edición de 1810 llegó a imprimirse, a cargo de la Imprenta Real. La estructura de las tablas impresas (90 páginas, 108 entradas – letras, palabras o frases – en la mayoría de las páginas, es decir 9720 entradas, en números redondos) y la expresión de los términos (mediante la conjunción de las cifras correspondientes en cada una de las 36 líneas y de las tres, o cuatro, columnas por página). [2]

It should be noted that the tables were handwritten and that only this 1810 edition was ever printed, by the Royal Printing House. The structure of the printed tables (90 pages, 108 entries – letters, words or phrases – on most pages, i.e. 9,720 entries, in round numbers) and the expression of the terms (by combining the corresponding figures in each of the 36 lines and the three or four columns per page). [2]

– – – – – – o – – – – – –

*En 1803, la responsabilidad de la dirección de las comunicaciones Telegráficas (hasta entonces la transmisión de señales era competencia de la Marina) recayó en un civil, de ascendencia italo-portuguesa, el científico Francisco Antonio Ciera (1763-1814), matemático, astrónomo, profesor de la Real Academia de Marina, quién acababa de concluir, en ese mismo año, un primer esbozo de los trabajos de triangulación geodésica de Portugal, emprendidos bajo su tutela en 1800, e interrumpidos en 1804. Aparentemente, la incorporación de Ciera obedecía más a su reputación científica y al interés del Regente (el futuro rey D. João VI), atraído personalmente por la telegrafía óptica, que a sus conocimientos específicos en la materia. / In 1803, responsibility for managing telegraphic communications (until then, signal transmission had been the responsibility of the Navy) fell to a civilian of Italian-Portuguese descent, the scientist Francisco Antonio Ciera (1763-1814), a mathematician, astronomer and professor at the Royal Naval Academy, who had just completed, in that same year, a first draft of the geodetic triangulation work in Portugal, undertaken under his supervision in 1800 and interrupted in 1804. Apparently, Ciera’s appointment was due more to his scientific reputation and the interest of the Regent (the future King João VI), who was personally attracted to optical telegraphy, than to his specific knowledge of the subject.[2]

**El «Corpo dos Telégrafos» según su reglamento constituyente constaba provisoriamente de las siguientes plazas / According to its founding regulations, the ‘Corpo dos Telégrafos’ provisionally consisted of the following positions: [3]:

1 Director General.

6 Oficiales 1ºs, Ayudantes del anterior

3 Oficiales 2ºs Ayudantes

17 Cabos Primeros

28 Cabos Segundos

64 Soldados

1 Director General. 6 First Officers, Assistants to the Director General 3 Second Officers, Assistants to the First Officers 17 First Corporals 28 Second Corporals 64 Soldiers

Fuentes:

1 – Paneles explicativos de la exposición en el Museo de Elvas (Portugal).

2 – «Sobrevuelo de la Telegrafía Óptica en Lusitania» – Gilles Mutigner (UCM), Revista Internacional de Historia de la Comunicación, nº 3, Vol.1, año 2014, pp. 140-170

3 – «Bicentenario do Corpo Telegráfico 1810-2010«, VV.AA., Lisboa, 2010

Imágenes:

a – Portada: Maqueta de telégrafo de bolas inglés. Museo de Elvas (Portugal).

b – Fotos del autor

Un comentario sobre “La telegrafía óptica en el frente de Portugal. Museo de Elvas (Portugal)”